Historical overview of grape growing in Manilva

Manilva’s history is deeply intertwined with viticulture. Although grapes likely grew here in Roman times (Manilva’s climate and soils were noted as ideal, and local olives, grapes and fish were exported across the Roman Empire, the organized cultivation of vineyards began after the Christian Reconquista. In 1530, the Duke of Arcos – lord of the area then governed from Casares – granted settlers land on the hill of Los Mártires (site of modern Manilva) to repopulate and farm the area. By 1549, there are records of the Council of Casares petitioning the Duke for permission to plant vines, marking the formal start of Manilva’s vineyard tradition. Through the 16th to 18th centuries, grape growing and wine production became the economic backbone of Manilva. The town’s Muscatel (Moscatel de Alejandría) grapes thrived in the white albariza soils (chalky marl also found in Jerez), and local wines and spirits (aguardiente) were produced in quantity. By the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, Manilva’s sweet wines (as part of the broader Málaga wine trade) were highly regarded and shipped to markets as far as Britain and France. An 18th-century boom in Málaga province vineyards (to which Manilva contributed) brought worldwide renown to Malaga’s “Mountain wine” (sweet Moscatel wine).

However, Manilva’s vineyards also faced devastating downturns. A first crisis hit around the 1860s, when the vines were struck by diseases and pests. The most destructive was the phylloxera plague (late 19th century) which wiped out nearly all of Manilva’s vines. By 1890, the once-prosperous vineyards lay in ruin and viticulture lost its importance – grape growing survived only on a small, subsistence scale. It was only in the 1920s, after decades of economic hardship, that Manilva saw a recovery: growers replanted vineyards using phylloxera-resistant rootstocks and introduced Moscatel de Alejandría on a large scale. This high-yield, large-berry Muscat grape became the dominant variety and transformed local production. Rather than focusing on wine as before, farmers found the big, sweet muscat grapes well-suited for fresh eating and sun-drying into raisins. Thus, by the mid-20th century Manilva’s reputation shifted from wine to table grapes and raisins.

The mid-20th century was a relative golden era for Manilva’s vineyards. By the 1950s–1960s, virtually the entire countryside was blanketed in vines. A local agrarian survey noted that out of approximately 440 hectares of suitable albariza land, 400 ha were under vine by the 1960s, with only 40 ha urbanized. Manilva was second only to the Axarquía (Málaga’s eastern region) in grape production in the province. Many families maintained small vineyards and the harvest was a community endeavor. Much of the production at this time was sold as fresh fruit or raisins, or made into a sweet moscatel wine for local consumption. Older residents recall that for decades, one of the few ways to taste “Manilva wine” was to buy it in jugs or plastic bottles from local cooperatives or markets – it was a rustic, often unfortified sweet wine consumed locally, as Manilva’s grapes were largely absorbed into the general Málaga DO wines (established in 1933) and not bottled under its own name.

By the late 20th century, however, Manilva’s vine culture faced a new challenge. The tourism and construction boom on the Costa del Sol in the 1970s–2000s led to mass urbanization of agricultural land. Vineyard owners, already aging and lacking a next generation to continue farming, found it lucrative to sell their lands to developers. As a result, vineyard area plummeted. In a span of a few decades, over 70% of Manilva’s vineyards were lost to urban development, leaving only about 150 hectares of vines by the 2010s. The once vine-covered hills saw golf courses, villas, and urbanizations arise, fundamentally threatening a centuries-old livelihood. By the early 21st century, grape growing in Manilva was at serious risk of extinction.

Nonetheless, the 2010s also brought signs of revival. Awareness grew of Manilva’s unique viticultural heritage and terroir, spurring efforts to preserve what remained. The local government and passionate individuals took action to rescue old vineyards and return to winemaking (see Modern Revival and Wineries below). Thus, after weathering cycles of prosperity and decline – from the 16th-century expansion to the phylloxera collapse, and from mid-20th-century abundance to late-20th-century shrinkage – Manilva’s wine culture is now cautiously re-emerging, blending tradition with new approaches.

Grape varieties, table grapes and raisin production

Manilva’s vineyards are especially known for the Moscatel de Alejandría grape (Muscat of Alexandria). This ancient white grape variety has large, golden berries with intense floral aroma and sweetness. It became Manilva’s signature grape during the 20th century replanting and remains the cornerstone of local production. Moscatel de Alejandría is versatile – historically used for sweet wines, it also serves as an excellent table grape and for raisin making. Manilva’s muscatel thrives on the albariza soil (a chalky marl that retains moisture) and under the unique microclimate: the town’s proximity to both the Mediterranean Sea and Atlantic influences (Strait of Gibraltar) provides steady sea breezes and mild temperatures. Local growers and enologists note that Manilva’s Moscatel grapes achieve exceptional size and sweetness, distinct even from the same variety grown in other Malaga regions. Argimiro Martínez, a vintner in Manilva, observes that the Moscatel here has a unique character “despite being the same type” as the Axarquía’s – thanks to Manilva’s terroir of chalky soil and maritime climate.

Table Grapes: A majority of Manilva’s grape output has long been destined for the table (consumption as fresh fruit). Well into the 2010s, it was estimated that roughly 70% of Manilva’s grape production is sold as fresh fruit (“uva de mesa”). At harvest time (early August through September), clusters of plump Moscatel are sold at roadside stalls and village markets, fetching about 1-1.5 € per kilogram locally. The fresh Muscat grapes are prized for their juiciness and rich sweet flavor. In addition to Moscatel, a minor presence of other grape varieties exists: for instance, a local white variety called “Doña María” has been grown specifically as a table grape (this variety is distinct from Moscatel and is known for its eating quality). A few red wine grapes like Syrah, Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot or Tempranillo have also been planted on a very small scale in recent years, but these are experimental; the vast majority of vines are Moscatel. Overall, the fresh grape tradition remains strong – during harvest season many Manilveños still enjoy eating the fruit and even hold competitions for the biggest grape bunch during the harvest festival.

Raisin Production: Grapes that are not sold fresh often go to raisin (uva pasa) production, a practice that became predominant in Manilva in the late 19th and 20th centuries. Moscatel de Alejandría is ideal for raisins due to its high sugar content and large berry size. In fact, after Moscatel was widely reintroduced in the 1920s, Manilva gradually shifted to specializing in sun-dried Muscatel raisins. By the 1980s, Manilva’s raisin output was significant and formed part of the famous “Pasas de Málaga” heritage. The traditional process involves laying bunches of grapes on esparto grass mats in the sun for several days to weeks, often on small terraced drying beds (locally called paseros). The hot Andalusian sun desiccates the grapes, concentrating sugars and flavors. Manilva’s dry late-summer weather and reflective light soil provide good conditions for this artisanal drying. The result is large, dark, glossy raisins with intense sweetness – a delicacy enjoyed locally and exported.

By the 21st century, roughly 30% of Manilva’s grape harvest was being dried into raisins (or sold for drying). These raisins are usually marketed under the umbrella of “Málaga Raisins” (Pasas de Málaga), a product that has a protected designation of origin. In 2017, the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) recognized the Málaga raisin production system (specifically acknowledging the Axarquía and Manilva Moscatel raisin tradition) as a Globally Important Agricultural Heritage System for its unique blend of history and sustainable practices. Interestingly, due to limited local processing facilities, a portion of Manilva’s raisin output in recent years has been handled by raisin producers from the Axarquía: growers from east Málaga sometimes bring laborers to Manilva, harvest the Muscatel grapes, dry them, and then sell the raisins as “Pasas de Málaga – Axarquía,” effectively obscuring their Manilva origin. Local vintners like Argimiro Martínez argue that if branded as “Manilva raisins,” these would fetch a premium, since Manilva’s larger size Muscatel grapes yield particularly plump, high-quality raisins. Efforts are underway to encourage direct marketing of Manilva-origin raisins to preserve their identity and add value for local farmers.

Aside from table grapes and raisins, a smaller share of the crop goes into winemaking. For much of the late 20th century, only a very limited amount of wine was produced in Manilva proper – mostly sweet Moscatel dessert wine made by a cooperative or a few families, often consumed locally. Any surplus wine grapes were typically sold to wineries in other Málaga regions (e.g. the Axarquía). It is only in the last decade that local winemaking has resurged (see below), creating new demand for wine grapes. As of 2014, only “a minimal export” of Manilva grapes to external bodegas existed, but today with multiple local wineries operating, a growing portion of grapes are vinified in Manilva itself.

In summary, Moscatel de Alejandría is the lifeblood of Manilva’s viticulture – supporting a dual economy of fresh fruit and raisin production, with a renewed interest in winemaking. This grape’s adaptability has allowed Manilva to be known for sweet Moscatel raisins (a famed local product) and, increasingly, boutique Moscatel wines, all derived from the same vineyards that overlook the Mediterranean.

Cultural traditions and festivals

Manilva’s grape-growing heritage is celebrated through local traditions and annual festivals that highlight the importance of the vine. The most important of these is the Fiesta de la Vendimia (Grape Harvest Festival), a beloved event held every year on the first weekend of September once the grape harvest concludes. This festival began in the mid-20th century (1960s) and has since become one of Manilva’s defining cultural celebrations.

The Vendimia festival is a vibrant mix of the sacred and the secular, reflecting both the gratitude for the harvest and the joy of the community. Festivities typically kick off on Saturday evening with a solemn Mass at the Santa Ana Church in Manilva, followed by a procession of the town’s patron, the Virgin Our Lady of Sorrows (Nuestra Señora de los Dolores). The statue of the Virgin is carried through streets decorated with grape bunches, as locals pray for the blessing of the new vintage. An offering of grapes is made and a contest awards a prize for the biggest cluster of grapes grown that year – a friendly competition among farmers.

On the following day (Sunday), the atmosphere turns decidedly festive. In the central Plaza de la Vendimia, visitors and residents gather for music, flamenco performances, horse rider parades, and plenty of food and drink. The highlight is the traditional grape treading (pisada de la uva) ceremony. In the late afternoon or evening, men in rolled-up trousers hop into a large wooden tub and tread freshly harvested Moscatel grapes by foot, just as Manilva’s ancestors did to extract juice. The first juice (mosto) of the year is collected and blessed, and then offered freely to all attendees – tasting the first young wine of the season is a cherished ritual. This public grape stomp is both symbolic and practical: it demonstrates old winemaking techniques and allows everyone to share in the product of the harvest. Tourists and locals alike line up to sample the sweet, unfermented grape must or the very young wine, along with fresh muscatel grapes handed out for tasting. The event fosters a sense of communal pride and connection to Manilva’s terroir. The Sunday of Vendimia usually ends with live bands and dancing late into the night, and the following Monday is observed as a local holiday to recover from the festivities.

In addition to the Vendimia, there are other customs that underscore the grape’s role in Manilva’s culture. Historically, nearly every farming family would set aside a portion of their grapes to make a small barrel of house wine or a batch of mistela (a sweet fortified must) for personal use. This ensured that even if most of the crop was sold as raisins or table grapes, the family would have wine for the table and for celebrations. The knowledge of pruning, drying, and winemaking was passed down through generations, contributing to a rich intangible heritage around viticulture. In recent years, the Centro de Interpretación Viñas de Manilva (CIVIMA) – the local Wine Museum – has been documenting these traditions, from old pruning knives and grape presses on display to photographs of past harvests and festivals. The CIVIMA itself has become a cultural hub, educating schoolchildren and visitors about Manilva’s grape-related folklore and traditional practices, thereby helping keep them alive.

Manilva also shares in broader Málaga province traditions like the Romerías (pilgrimages) and Día de San Isidro (Patron of farmers), where local farmers may decorate carts and sometimes include grapevine motifs or distribute grapes and raisins as part of the feasts. While not unique to Manilva, these events reinforce the identity of Manilva as an agricultural community.

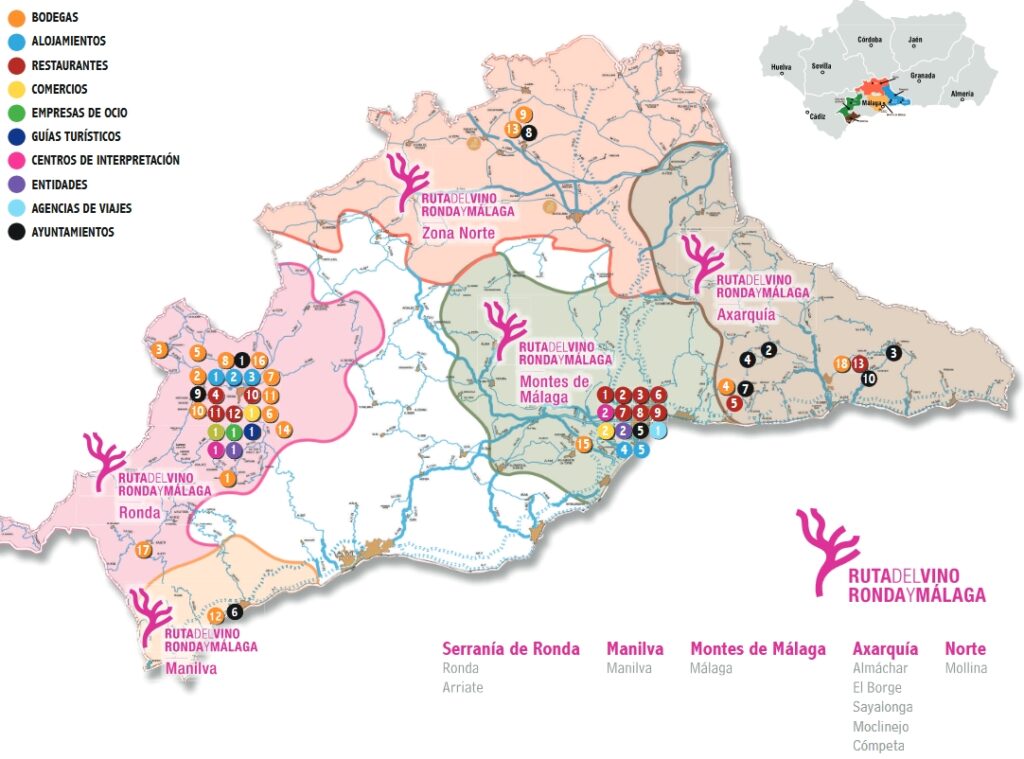

Gran Ruta del Vino de Málaga

Perhaps the most significant recognition of Manilva’s grape culture came in recent years when Manilva was included in the “Gran Ruta del Vino de Málaga” (Grand Wine Route of Malaga) – a tourism initiative linking the key wine-producing areas of the province. Manilva’s inclusion is based on its extraordinary history with Moscatel grapes and its revived wineries, marking it as a “must-visit” wine town alongside Ronda and Axarquía. This has further elevated local pride and spurred annual events like wine tastings, vineyard tours, and even a small harvest fair aimed at gastronomic tourism. All these festivals and traditions, from the centuries-old foot treading to new wine tours, weave the grape into Manilva’s social fabric and yearly calendar, ensuring that the town’s motto could well be “A Manilva, a por uvas” (To Manilva, in search of grapes).

Modern Revival and Current Wineries in Manilva

In the last decade, Manilva has witnessed a renaissance of its wine industry. After years of decline, a handful of passionate winemakers and entrepreneurs have begun reviving local vineyards and creating quality wines, determined to re-establish Manilva’s identity as a wine town. This modern revival builds on the town’s heritage while introducing updated techniques and enotourism. Today, there are several active bodegas (wineries) in Manilva, each with its own story, but all sharing a commitment to the Moscatel grape and the preservation of local viticulture. Below is an overview of the current operating wineries in Manilva, including their history, production, and wines:

Bodega Nilva Enoturismo (Nilva Winery)

Bodegas Nilva is at the forefront of Manilva’s wine resurgence. Founded in 2011–2014 as part of a local initiative, it began when Argimiro Martínez Moreno, an agronomist from Albacete, arrived to teach an enology course and was enchanted by Manilva’s viticultural potential. Seeing abandoned old vineyards and a “terroir único” (unique terroir) being forgotten, Argimiro decided to stay and spearhead a project to save Manilva’s vines. He obtained a municipal concession to use an old cooperative winery building, and by 2015 had established Nilva Enoturismo SL, which comprises a boutique winery (Bodega Nilva) and the CIVIMA wine interpretation centre. The winery is located in Manilva village (next to the museum) and also manages a 2.8-hectare vineyard known as Viña del Peñoncillo on the slope of Loma de Pampanito between the town and coast. Some of the vines in this vineyard are over 50 years old, grown as low bush vines nearly crawling on the ground to resist strong coastal winds. All cultivation is organic and focused on Moscatel de Alejandría.

Bodega Nilva is equipped with modern winemaking facilities (stainless steel tanks, pneumatic press, temperature control, lab, etc.) and has an annual production capacity of about 6,000–7,000 bottles (around 4,500 liters). Argimiro’s approach combines traditional knowledge with modern enology. Nilva specializes in 100% Moscatel wines, crafted in multiple styles. Its flagship is Nilva Moscatel Seco, a dry white wine that surprises those expecting sweetness from Moscatel – it is fermented dry to a crisp, aromatic white. Tasters describe it as fruity, floral, and fresh with a touch of saline minerality from the maritime climate. In fact, the very first vintage (2016) of Nilva’s dry Moscatel won a national award as Spain’s Best Varietal White Wine in its category, beating over 200 other wines – a testament to its quality. Nilva also produces a semi-sweet (semi-seco) Moscatel and a sweet dessert Moscatel in limited quantities. These sweeter wines are made by sun-drying the grapes on mats to concentrate sugars: one is made from grapes dried about 2 days (yielding an off-dry wine), and the other from grapes dried up to 6 days (yielding a rich natural sweet wine). All Nilva wines carry the Málaga D.O. or Sierras de Málaga D.O.P. designation as appropriate. The dry Moscatel (Nilva Seco) falls under D.O.P. Sierras de Málaga, and the naturally sweet Moscatel under D.O. Málaga. Production is still boutique-scale – for example, in 2020 about 6,000 liters were made – but the focus is on high quality over quantity.

Beyond winemaking, enotourism is a key aspect of Bodega Nilva. The winery operates the Centro de Interpretación “Viñas de Manilva” (CIVIMA), a museum dedicated to the local vine culture. Visitors can tour exhibits of old farming tools, historical photos, and even elements of Manilva folklore related to wine. After the museum, guests visit the working winery to learn about modern Moscatel winemaking (often even seeing traditional grape treading if in season). Tastings are offered on a terrace with views of the Mediterranean. Nilva Enoturismo has innovated experiences like vineyard tours with wine picnics and even partnered with local fishermen to do a combined “sea and wine” boat tour with wine tasting on board. This integration of wine, history, and tourism earned Nilva international recognition, including awards for wine tourism. Argimiro’s vision goes beyond his own bodega: he has trained local students in oenology and actively encourages others to start small wineries, hoping to see “10 boutique bodegas” in Manilva in the future to revive the landscape and give farmers a reason to keep their vines. Bodega Nilva’s success – from award-winning wines to drawing visitors from afar – has been the cornerstone of Manilva’s wine revival, proving that the town’s Moscatel grapes can yield world-class wines when given proper care.

Bodegas Manilva

Another major player in Manilva’s wine rebirth is Bodegas Manilva, a small winery founded in 2016 by three local families. Among them are Elena Revilla and her husband Diego Amado, who have been public spokespeople for the project. These families were longtime grape growers who, inspired by Argimiro’s example and by their own successful experiments, decided to vinify their Moscatel harvest rather than sell it off. After an “experimental” first batch in 2016 that showed promise (they named that trial wine “Kalma” to signify the patience and calm needed), they formally established Bodegas Manilva. The bodega is located in the town (Calle Mar 76), and they source grapes from old Moscatel vineyards on the Loma de Pampanito — the same favorable slope that Nilva cultivates, known as the southernmost vineyard land in Europe. Bodegas Manilva prides itself on using 100% Moscatel de Alejandría from “viña vieja” (old vines) on white albariza soil, emphasizing the pure expression of Manilva’s terroir in their wines.

Their flagship wine, “Kalma”, is a dry Moscatel white. It is crafted in a modern style: fermented fully dry to about 13% ABV, yielding a fragrant yet crisp wine. Kalma was launched commercially in 2017, and by 2018 it had earned a D.O. Sierras de Málaga certification and positive reviews for its aromatic intensity and balance. Bodegas Manilva has since expanded its range. They produce a sweet Moscatel dessert wine called “Pampanito”, named after the Pampanito vineyard hillside.

Pampanito is a classic Málaga-style naturally sweet wine made from sun-dried Moscatel grapes (with D.O. Málaga status). In 2023, the family introduced “Kalma Rosé”, an innovative rosé wine that actually steps outside the Moscatel domain: it is made from Garnacha grapes (both red and white Grenache) to create a rosé with a 13.5% natural alcohol, described as having floral freshness and a striking light ruby hue. The choice to use Garnacha was bold (“we departed from the traditional Moscatel to try something new,” Elena Revilla noted), but it demonstrates Bodegas Manilva’s experimental spirit. The first release of Kalma Rosé in 2023 was only 800 bottles, and it was unveiled with fanfare in Manilva before being offered to broader markets – the owners said they wanted it to “start its journey in the town that saw it born, before it begins its walk through the world”. This suggests ambitions to distribute Manilva wines internationally.

Bodegas Manilva’s wines carry the local brand proudly – for example, their labels often highlight “Manilva – Costa del Sol”. The dry Moscatel Kalma and the Rosé are under D.O. Sierras de Málaga, while the sweet Pampanito is under D.O. Málaga. They remain a small-batch producer, largely handcrafting wines. They also produce an organic version of Kalma (sometimes marketed as Kalma Organic), reflecting a commitment to sustainable practices. Despite its youth, Bodegas Manilva has gained attention: their table wines have been showcased in provincial wine events and even at the FITUR international tourism fair as part of Málaga’s wine tourism promotion. Local media have praised the initiative for “doing something so beautiful for Manilva”, and the winery often collaborates with the Town Hall on agricultural and tourism events.

In essence, Bodegas Manilva represents the new generation of local vintners – people whose families grew grapes for decades and who now bottle that heritage. With Kalma (dry), Kalma Rosé, and Pampanito (sweet), the winery offers a trio of wines that cover the spectrum of Moscatel expression. As of now, volumes are limited (in the low thousands of bottles annually), but demand is growing. The success of Kalma has even led to local supermarkets stocking Manilva’s own wine – a sight that would have been rare prior to 2014, when one could hardly find bottled Manilva wine at all. The project’s success is inspiring other vine-owning families to consider small-scale winemaking, further contributing to the town’s wine renaissance.

Bodegas Bocanegra

Bodegas Bocanegra is a unique winery in Manilva that bridges the past and present. It is run by the Bocanegra family, who claim a winemaking heritage in Manilva dating back to 1860. Indeed, the Bocanegra are a longstanding local family who for generations tended vines and made traditional Moscatel wine. In recent years, under the stewardship of siblings like Gonzalo Bocanegra, the family bodega was rejuvenated and officially launched as a commercial winery. The bodega is located in Manilva town (C/ Mar 31), with vineyards presumably in the surrounding countryside (the family’s rural property is in the area of “Las Esillas”. Bodegas Bocanegra has embraced modern winemaking while honoring tradition – their winery was carefully restored to blend old craftsmanship with new technology. The mission statement highlights “preserving the essence of our heritage while innovating to produce wines of the highest quality”.

The Bocanegra winery specializes in “vinos jóvenes y frescos” – young, fresh wines – made exclusively from Moscatel de Alejandría grown in Manilva. They proudly call their products “Vinos monovarietales de Moscatel: La Esencia de Manilva” (single-varietal Moscatel wines: the essence of Manilva). Rather than the classic sweet fortified wines one might expect from Malaga Moscatel, Bodegas Bocanegra focuses on unfortified styles that showcase the grape’s aromatic qualities in a lighter form. For example, two of their flagship wines are “El Barbudo” and “Doña María,” both made 100% from Moscatel grapes. El Barbudo (which means “The Bearded One”) and Doña María are branded wines that likely pay homage to local history or family figures – possibly an ancestor nicknamed El Barbudo, and Doña María could reference either the grape variety of that name or a matriarch. These wines are described as having a distinctive character with tropical fruit notes, white flower aromas, and a touch of sweetness on the palate – essentially aromatic young whites that are very approachable. The winery emphasizes careful grape selection and modern vinification to ensure clean, expressive flavors. Fermentations are done in stainless steel to retain aroma, and the wines are likely bottled within a year of harvest to be enjoyed young.

Bodegas Bocanegra also continues to produce a sweet wine in the traditional manner. They have mentioned a semi-seco (semi-dry) Moscatel made from grapes dried 2 days, and a sweet dessert Moscatel from grapes dried ~6 days (similar to Nilva’s range, suggesting that the overall approach to sweet wine is common among Manilva vintners). While their product lineup is not widely published, the mention of these styles in a tourism guide implies Bocanegra offers multiple Moscatel expressions – likely a dry/fragrant white, a medium sweet, and a richer sweet, aligning with local tradition.

The Bocanegra family’s efforts gained wider attention when they presented their wines at FITUR 2023, indicating a push to gain international profile. They proudly marketed their wine as an authentic product of Manilva at this globally attended tourism fair, aligning with the province’s enotourism promotion. Locally, Bodegas Bocanegra is often cited as an example of “tradición ancestral” (age-old tradition) being carried forward successfully. A video interview with Gonzalo Bocanegra on Manilva’s town media highlighted the family’s pride in their heritage and commitment to continue the magic of grape and wine, generation after generation. The winery welcomes visitors for tastings by appointment and shares the unique story of a family that never gave up on wine, even when commercial winemaking in Manilva had vanished.

In summary, Bodegas Bocanegra stands as the old soul of Manilva’s winery group – it leverages a 19th-century legacy, has been renewed with 21st-century techniques, and produces limited-edition wines that capture Manilva’s “essence” in every bottle. Their use of brand names like El Barbudo and Doña María for Moscatel wines shows a flair for local storytelling. Together with Nilva and Bodegas Manilva, Bocanegra completes the trio of active Manilva wineries restoring the town’s winemaking renown.

Bodegas Ana García

In the heart of Manilva, in the province of Málaga, you’ll find Bodegas Ana García, a true gem of winemaking that combines tradition, hospitality, and a passion for wine. Located at Camino Chorro Manso, 12, this family-run winery is operated by Esther and Manuel, who offer visitors an authentic and personal experience.

The winery produces three types of wine from Muscat grapes: a dry white, a semi-sweet rosé, and a sweet dessert wine, all crafted from century-old family vines. During visits, the hosts share the winemaking process and offer tastings accompanied by homemade dishes prepared with local ingredients. The personalized attention and welcoming atmosphere make every visit unforgettable.

Bodegas Ana García is wheelchair accessible, ensuring that all visitors can enjoy the experience. The winery has received excellent reviews, with a rating of 4.9 out of 5 on Google, praised for both the quality of its wines and the warmth of its hosts.

Reputation, exports, and the future of Manilva wines

Manilva’s wines and grapes have oscillated between obscurity and renown over the centuries. Historically, as part of the Málaga wine region, Manilva contributed to wines that were celebrated worldwide. In the 18th and early 19th century, Málaga’s sweet Moscatel wines (often called Mountain wine in Britain) were highly prized – they featured on prestigious wine lists in London and Paris, sometimes commanding very high prices. It is likely that some of the Moscatel for those wines came from Manilva’s vineyards, especially before phylloxera. However, those wines were generally branded simply as “Málaga,” so Manilva’s name did not stand out internationally at that time. Manilva’s raisins too were part of the famous Málaga raisin trade, exported to Northern Europe for use in plum puddings, cakes, and as table snacks. In that sense, Manilva’s produce has long traveled beyond Spain’s borders, albeit anonymously under the Malaga banner.

In the 20th century, as local winemaking waned, Manilva’s grapes still found their way into Jerez sherry (some Manilva muscat was used for blending or distillation) and into Málaga wine blends, but again, the town remained a “hidden contributor” rather than a known origin. Locally, vino dulce de Manilva had a humble reputation – a hearty sweet moscatel appreciated in the region but hardly known elsewhere. It wasn’t until the recent revival that “Vino de Manilva” has begun to carve out its own reputation.

Today, with dedicated wineries and bottled products, Manilva is starting to gain recognition in the wine world. The quality of these boutique wines has been validated through awards and press coverage. In 2021, Nilva’s dry Moscatel 2020 won the “Sabor a Málaga” award for Best White Wine (D.O. Sierras de Málaga) in a provincial blind tasting competition. This is a significant accolade given it was a contest among many Malaga wineries. Such awards help put Manilva on the map as a distinct source of excellent Moscatel wines. Wine enthusiasts now sometimes seek out Manilva’s Moscatel seco as a unique product – a few niche wine sellers in Europe have started carrying it, and oenologists have noted its Fino-like crispness (attributed to the albariza soil) as something intriguing.

The local reputation of Manilva wine has improved dramatically: once seen as a simple farmhouse wine, it is now proudly served at upscale restaurants on the western Costa del Sol. The Malaga provincial marketing brand “Sabor a Málaga” features Manilva wineries as key representatives of the Moscatel tradition. Manilva’s inclusion in the official Ronda & Málaga Wine Route means it is promoted alongside Ronda’s reds and Axarquía’s dessert wines, giving it parity in tourism literature.

Exporting Manilva’s wines

In terms of export activities, volumes are still small, but there are steps in that direction. Bodegas Manilva hinted at taking their wines “on a journey around the world” – indeed, by attending international fairs, they are seeking importers. Some Manilva wines have begun to be exported in limited batches: for example, the Kalma Moscatel Seco has been spotted on sale in specialty wine shops in the UK and Germany (marketed as a rare Andalusian dry Moscatel). The sweet wines like Pampanito and Nilva’s dessert Moscatel could tap into the niche market for natural sweet wines, potentially appealing to consumers of Sauternes or Tokaji. Additionally, Manilva’s raisins continue to be exported, now under the prestigious D.O. Pasas de Málaga – these raisins, including those from Manilva, were recently highlighted in EU agri-food promotions as a gourmet product. The SIPAM distinction in 2017 drew international attention, with Manilva’s raisin farmers mentioned in FAO reports.

One challenge for greater export penetration is scale: the combined output of all Manilva bodegas is probably under 20,000 bottles annually at present. However, as more growers consider winemaking, this could grow. Argimiro’s vision of 10 micro-wineries each making singular wines could yield a diverse palette of Manilva wines – dry, sweet, perhaps even sparkling Moscatel in the future – that collectively build “Manilva” as a recognizable origin. The local government is supportive: there are plans to preserve remaining vineyard land through agricultural subsidies and to possibly obtain a special geographic indication for Manilva within the D.O. structure (for instance, similar to how “Serranía de Ronda” is a sub-region, one day “Costa Occidental – Manilva” might be highlighted). Gaining such official recognition could further elevate the town’s reputation and protect the name “Manilva” on wine labels.

Consumer response to Manilva wines has been very positive. Tourists visiting the area often express surprise that vineyards exist so close to the beach resorts, and they enjoy the contrast of sipping a locally grown Moscatel while looking out at the Mediterranean. The unique story – vines that nearly vanished due to tourism now coexisting with it – resonates with people. This narrative has even been covered in travel media, calling Manilva an “unexplored gem” with a wine tradition being reborn.

Looking to the future

Looking ahead, the future of Manilva’s wine industry appears hopeful. Key factors for success will be: continuing to improve quality (through modern viticulture and enology), securing the next generation of growers (to prevent any further loss of vineyards), and smart marketing that leverages both tradition and innovation. The current winemakers are already collaborating; for example, all three main bodegas are part of the Manilva Wine Association and often present jointly at fairs. There is talk of creating a Manilva Wine and Raisin Interpretation Route linking vineyards, the museum, and even old pasero drying fields as a comprehensive agro-tourism experience.

In conclusion

In conclusion, Manilva – once known only as a footnote in the larger Málaga wine region – is forging its own identity as a source of exquisite Moscatel grapes, delectable raisins, and increasingly high-quality wines with a story. From the Duke of Arcos’s 16th-century vineyards to the calamity of phylloxera, from the humble raisin farmers to the modern enologists, the journey of Manilva’s viticulture is rich and continuing. The town’s local and international reputation is on the rise: locally, Manilva is again proud to be “tierra de uvas” (land of grapes), and internationally, wine lovers are beginning to recognize “Manilva Moscatel” as something special. As one local vintner put it, “If we want a future, we must bet on an excellent product that pays the grower what they deserve” – in Manilva, that product is well on its way to being the pride of the town and a delight to the world’s palates.

![]()